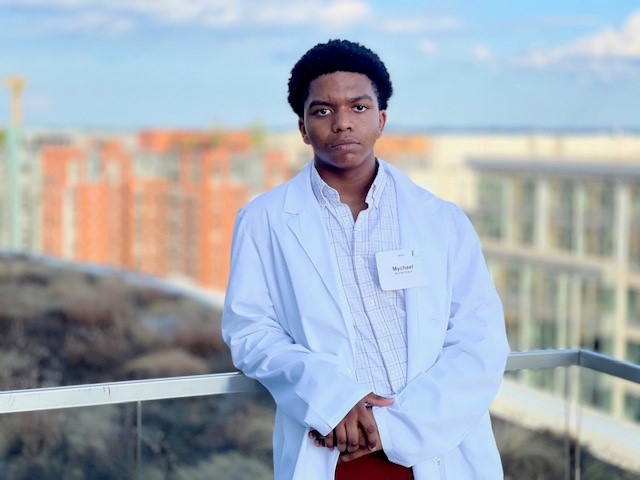

The morning of Thursday, June 1, 2023 started like any other average school day for 17-year-old Mychael Brown. But when the high school junior was preparing to get off a train at Foggy Bottom metro station in Northwest Washington, D.C., he noticed a man in the same car starting to choke and fall unconscious. Another passenger had warned him to stay away.

Still, Brown rushed toward the man, put him in a recovery position, waited for the vomiting to stop before doing CPR compressions, and stayed behind until emergency health workers arrived. Had no one helped, the man’s vomit would likely have obstructed his airways and killed him. Brown arrived thirty minutes late to school that day but said that the feeling of giving his all to save someone’s life was an incomparable first.

He says that it will be far from his last time.

Brown, a rising senior at the School Without Walls, is a member of the Young Doctors Project. This D.C.-based nonprofit invests in 13 to 18-year-old students who predominantly identify as Black or Latino men wishing to pursue a medical career. On Sunday, June 25, the Young Doctors Project hosted its 11th annual White Coat celebration of the newest cohorts of “Young Doctors” on the rooftop terrace of the American Association of Medical Colleges building in the heart of Washington, D.C.

Beyond equipping participants with career resources, the directors of the selective program are ushering in a counter-narrative to the portrayal of men of color in the news and calling attention to racial and socioeconomic inequalities in the physician world, where less than 3 percent of individuals are Black men. In D.C., the country’s 15th most segregated metropolitan area, the average life span of residents across some neighborhoods can vary by decades.

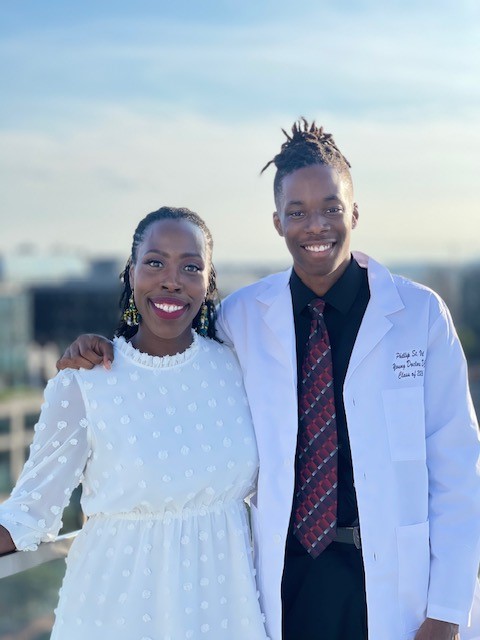

“Ever since 2020, with George Floyd and the reignition of the Black Lives Matter movement, we have just always seen a negative image of Black men on T.V. and in media. To be in this space — it is uplifting,” said Christine St. Vil, a parent of a Young Doctor. “My son [is] able to be in his program and not only see people that look like him but work with people that look like him and receive mentoring from people who look like him.”

For St. Vil, representation is more than face value; it helps save lives. As a mother, the alarming statistics of disproportionate Black maternity deaths — 2.6 times greater than non-Hispanic, white mothers — are a forever pang in the mind. A September 2020 study found that compared to their white counterparts, Black newborns are three times as likely to pass away in the hospital if they had white doctors.

According to Young Doctors co-founder Dr. Malcolm Woodland, their intimate understanding of Blackness and knowledge of nuances surrounding barriers to Black wellness makes Black doctors willing to take a more significant chance on their patients of color. A Southeast D.C. native and now a forensic psychologist still in the city at large, where he has sat across incarcerated African American men countless times and saw firsthand the correlation between poverty and disease, he knew the potential impact of a free program as an engine of social mobility for young boys.

Nonetheless, recognizing painful inequalities was only one part of Sunday’s ceremony. Dr. Malcolm Woodland said that celebratory moments are “rare” in recognition of Black achievement, and society often excludes these moments from the effort of creating an enduring legacy in the community.

A Tougaloo College and Howard University graduate, Woodland is a long-time researcher of the school-to-prison pipeline, focusing on youth development and forensic assessment challenges confronting African American boys. The idea for Young Doctors had been marinating in his head for years before he finally received a startup grant from the D.C. Social Innovation Project to pursue the program. Growing up around family members who worked in TRIO, a federal program that provides student support resources to first-generation and low-income students and students with disabilities, he modeled the program after Upward Bound.

In addition to sitting in on weekend lessons with current medical students, enrolled Young Doctors are slated to spend four weeks every summer on the Howard University campus, where they will shadow doctors, explore preliminary research skills, and rotate across hospital departments. In the third year, they will work closely with community clinics to measure patient blood pressure and glucose levels. They receive college access support and entrance exam preparation in the fourth year.

For some, like Christine St. Vil’s son Phillip Jr., the trip marks the longest time he will be away from his parents, but she is confident that he will find his new home away from home in an environment of like-minded peers.

This year, the program welcomed members from Roanoke, Va., and New York City for the first time. At the ceremony, members of previous Young Doctor cohorts, many of whom are currently in graduate medical programs and will continue to serve as mentors, helped adorn each participant in the new class with a white coat. As Woodland pointed in the directions of two different wards from the rooftop, he said that he dreams of the day when both sides of the city are given the same opportunities for a long, healthy life.

“It’s nice because the other kids and parents see the kid in the white jacket with the stethoscope around his neck,” Woodland said. “He becomes a real healing body that people in the neighborhood visit when something is wrong. That is not how society often understands black and brown boys in their neighborhoods.”

“I don’t know if [the man I helped] lived or died. But at least I kept him alive enough for him to have a chance to live,” said Mychael, an aspiring cardiologist or anesthesiologist. “I would say I have a good mind, and whatever I want to change, I will put my mind to.”