When people ask me about my work, they often wonder if my motivation stems from being a low-income, first-generation college student myself. I am always quick to tell them that it was actually my parents who blazed that trail.

My mom’s story begins on a farm in South Carolina. Neither of her parents had the opportunity complete their high school educations. Rather, like most other children in Southern black families, they abandoned school in their teens in order to work—my grandmother on her family’s farm and my grandfather as a sharecropper. After my grandfather was drafted to serve in World War II, my grandparents decided to seek better opportunities “up North.” So, along with six million other African Americans participating in the Great Migration, they relocated to Connecticut when my mom was a child, eventually finding work in factories and mills. Although it was possible to obtain a promising middle-class lifestyle without a college degree, my grandparents did not want my mother to have to “work with [her] hands” as they did. Recognizing her potential, they urged her to pursue higher education. Although she graduated at the top of her high school class, like many of our own TRIO students emerging from under-resourced high schools, she found herself woefully unprepared for the rigors of college. She persevered and ultimately, she earned her associate’s degree from Quinnipiac College (now Quinnipiac University). Armed with her degree, she worked her way up to becoming a senior secretary for IBM Corporation.

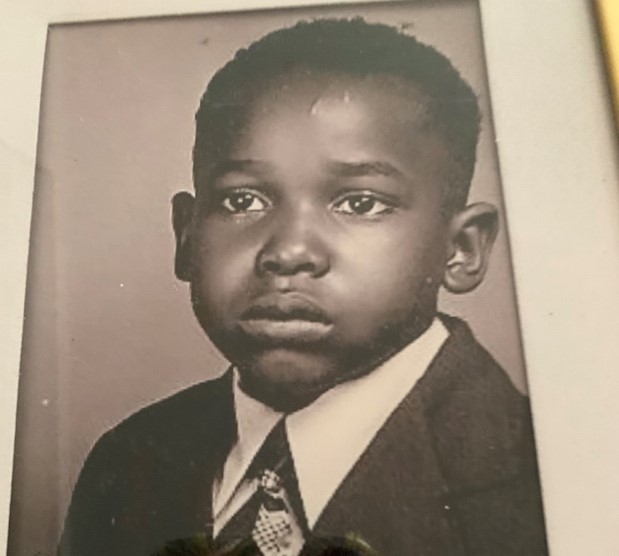

My father’s journey also embodies the pursuit of education and upward mobility. After his own father’s tragic murder shifted his family from relative comfort into poverty, my grandmother moved from New York City to Connecticut with her two young sons. Higher education really wasn’t on my father’s radar. Growing up in the housing projects, his focus was squarely on earning money. Like many of his peers, he went into manual labor, pursuing jobs at a meat packing factory and aircraft manufacturer. His trajectory shifted when a manager recognized his talent and encouraged him to pursue “a good clean job” — and that required a higher education. For most of my childhood, my father took night school courses at the University of New Haven and eventually earned his master’s degree. Meanwhile, he worked his way up to becoming a branch manager for the local telecommunications carrier—a role held by only a few African Americans at that time.

Growing up, my brother and I absorbed our parents’ commitment to education and remained united by their determination. Although we were ineligible for TRIO, my brother had the good fortune to participate in a state-funded program, Conn CAP (Connecticut Collegiate Awareness and Preparation Program). Modeled after Upward Bound, Conn CAP had a teacher preparatory focus and forged the pathway to his role as a high school teacher today.

In a household imbued with the value of higher education and all of the accompanying middle-class values that it conveyed, my journey to college was, in many ways, paved for me. It was never a question of whether I would go to college, but where I would go to college. I’m sure it surprises no one who knows me personally that I was a happy and willing passenger on this ride – making all of the important pit stops along the way like honors courses and extra-curricular activities. It was, in fact, this pursuit of assembling the perfect Ivy League college application that sparked my passion for service and introduced me to what would become my calling.

Most connotations of Connecticut bring to mind elegant golf courses, boat trips along the Long Island Sound, and bedroom communities for high powered New Yorkers. My hometown of New Haven, however, was and is one of the poorest cities in the state. (Currently, the poverty rate in New Haven is more than double that of the state and 92% higher than the U.S. average.) Sharing park benches with the homeless while waiting for the school bus was a regular occurrence for me. This exposure motivated me to find ways to try and help, delivering food and clothes with a weekly service group in my high school.

While I’m certain that these gestures were appreciated by those in need, this regular service experience crystalized for me the meaning of the oft-quoted proverb: “Give a man to fish, and you feed him for one day. Teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.” My desire to work towards more permanent impact was only intensified by my service as a representative on the New Haven Board of Young Adult Police Commissioners (YAPC). Serving on YAPC gave me direct access to the Chief of Police, Mayor, and other elected officials who often sought our advice on various policies impacting the city’s youngest residents. This was the beginning of my involvement in public policy and planted the seeds for my future career as an advocate.

My youthful scholarship and service efforts were rewarded by admission to Yale University, where I majored in Political Science, and then Georgetown University Law Center (GULC), where I pursued a curriculum that placed a particular emphasis on legislative advocacy. I spent most of my time as a law student serving as a law clerk at legal aid clinics and loitering outside of the GULC’s Office of Public Interest and Community Service. Yet, I could not resist the urge to follow in lock-step behind my classmates to don a dark suit and trot off to private practice following graduation.

I served as an associate for two-and-a-half years at a large law firm in Washington, D.C. While this was intellectually stimulating work, it did not feed my hunger to serve. This morsel came in the form of a new client to the firm – the Council for Opportunity in Education.

Thanks to a fortuitous introduction by a partner in the firm’s Education Practice Group, I joined COE in 2007 as its director of congressional affairs. I was inspired by their mission to ensure all students can pursue higher education, regardless of background; something that reminded me so much of the experience of my parents. I was also grateful to have the opportunity to fulfill my desire to engage in meaningful work with long-term social impact.

Much like our TRIO professionals, the ability to help transform the lives of thousands of students continues to drive me to this day.

My new role as the president of COE is both exhilarating and daunting as I know I will encounter new challenges that have broad implications for our students. However, I am ready to serve and continue the work necessary to ensure success for our first-generation, low-income students in getting to and through college. I’m also excited by the many new initiatives of the Council that seek to aid them even after they walk across the graduation stage.

Ultimately, my journey from a second-generation college student to an educational advocate is a testament to resilience, the pursuit of excellence, and the unwavering belief that education can transform multiple generations. With dedication and collaboration, we can ensure that all students have the chance to succeed and thrive, no matter their background.